A Blueprint for Resilience: What Bangladesh's Youth Teach Us About Climate Action

Posted by Mikko Tamura • Feb. 8, 2026

In Bangladesh, climate change is not a distant threat—it is an everyday reality. From flooded alleyways in informal settlements to rising heat trapped inside densely packed homes, climate impacts shape how people live, move, and survive. Yet for many of the communities most affected, these realities remain largely invisible in formal planning spaces. Data is often scarce or outdated, local knowledge is overlooked, and young people—despite standing at the frontlines of climate impacts—are rarely trusted as decision-makers.

The Climate Resilience Fellowship (CRF) was created to challenge this pattern.

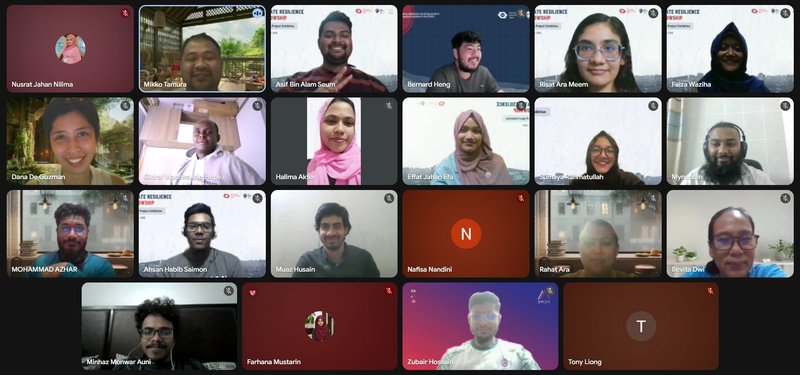

Jointly led by the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team’s Open Mapping Hub - Asia-Pacific and World Vision Bangladesh, with support from NetHope, CRF placed local youth at the center of climate resilience work. The fellowship was grounded in a simple but powerful idea: when young people are equipped with the right tools, mentorship, and space to lead, they can translate lived experience into meaningful, community-owned climate solutions.

Over three months, fellows from across Bangladesh—some from climate action backgrounds, others from open mapping and data communities—came together to implement community-driven projects that strengthened local climate resilience. What united them was not simply technical interest, but a deep connection to the places most affected by climate risks. Many lived in or near informal settlements in Dhaka and Chattogram, where flooding, heat stress, water scarcity, and public health risks are daily constraints on dignity and opportunity. These were not theoretical problems to be studied from a distance; they were realities the fellows and their communities navigated every day.

View of a waste disposal site in Duaripara, one of the informal settlements in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where several fellows’ projects took place | Photo: WeatherWise: মেঘবন্ধু (MeghBondhu)

The fellowship journey was intentionally designed to move beyond training for training’s sake. Prior to the project implementation, fellows were immersed in a learning process that blended climate science, open mapping technologies, and people-centered approaches. They learned how to collect and interpret data ethically, how to work with communities rather than extract from them, and how to design interventions that were realistic within the constraints of time, funding, and local capacity. Just as importantly, they were trained in project implementation, financial accountability, and reporting—skills often missing from youth-led initiatives, yet essential for long-term credibility, partnership, and scale.

Fellows gathered to pitch their project ideas to mentors and guest panelists during the in-person boot camp | Photo: Rajib Mahmud / World Vision Bangladesh

A pivotal moment in the fellowship came during an in-person boot camp hosted at the World Vision Bangladesh office. For many fellows, this was the first time they entered a professional development space where their ideas were treated not as “youth projects,” but as viable responses to real climate challenges.

The boot camp fostered collaboration, sharpened project plans, and strengthened fellows’ confidence as leaders accountable to both communities and institutions. To mirror real-world funding and review processes, CRF invited guest panelists from the American Red Cross and the Bangladesh Red Crescent Society, alongside mentors and trainers, to support practice pitching sessions—offering critical feedback and exposing fellows to humanitarian and development perspectives.

As fellows moved into project implementation, the diversity of their approaches became one of CRF’s strongest signals of impact. Rather than converging on a single solution, fellows responded to the specific risks and capacities of their communities. Some focused on water security, installing community-based rainwater harvesting systems and training residents to maintain them collectively. Others tackled extreme heat, distributing heatwave kits and working with households to adopt practical, low-cost cooling and preparedness measures. Several teams addressed urban flooding and waste, organizing community-led clean-ups, implementing recycling and waste-segregation programs, and mapping drainage blockages to reduce waterlogging and health risks.

Innovation also took digital forms. Fellows developed climate chatbots and early-warning information tools, co-designed with community members to ensure accessibility and trust. Through open mapping, informal settlements were placed onto the map—sometimes for the first time—making risks, services, and gaps visible to local authorities and NGOs. Across projects, fellows led climate awareness and preparedness campaigns, translating complex climate information into locally relevant, actionable knowledge.

Mapping, in this context, became more than a technical exercise. It served as a bridge—connecting data with lived experience, and communities with institutions. In places often excluded from formal systems, maps supported dialogue, advocacy, and negotiation, helping communities articulate their needs and priorities in ways decision-makers could engage with.

Through mapping, fellows identified community-level risks, allowing them to design more informed, data-driven solutions. The maps and data also became powerful advocacy tools, helping communities better understand local risks. | Photo: The Resilient Trashformers, D-PACT, and OSM Academy

The impact of the Climate Resilience Fellowship cannot be measured by outputs alone—but the numbers tell part of the story. Nineteen fellows successfully completed the fellowship, and nine capstone projects were fully implemented across Dhaka and Chattogram. Through these initiatives, 1,312 community members were trained on climate change awareness, while eight development actors and partner organizations strengthened their capacity to use open-source and open mapping data in climate and resilience work.

Beyond participation, communities gained practical skills and a stronger voice in local resilience efforts. Youth gained confidence to lead, to engage institutions, and to be recognized as legitimate actors in climate response. Women and marginalized groups were not only included, but positioned as leaders in sustaining solutions.

Fellows presented their projects at the Capstone Project Exhibition. Watch the event recording here.

CRF also created pathways beyond pilot implementation. The fellowship concluded with an online pitching session, where all nine project teams presented their work to local and international guests, practitioners, and funders. This space emphasized learning and connection—offering strategic feedback, surfacing lessons, and opening doors to future collaboration.

Several projects have since continued to gain traction. Research conducted by Nusrat Jahan Nilima and Minhaz Auni’s team has been invited into NGO learning spaces for further exploration, while the MAP 4 RESILIENCE project, built around the PLASPIN Model (reward-based recycling system) by Sumaya Rahmatullah and Effat Jahan Efa’s team, has received invitations to present its approach to organizations exploring scalable, community-driven resilience and waste management models. These moments underscore the value of investing early in youth-led innovation—before ideas are fully formed, when they are most responsive to community needs.

In their experimental research, Nusrat and Minhaz tested four low-cost solutions to analyze their effectiveness in reducing temperature. | Photo: Ishrat Jahan Eshita, Nusrat Jahan Nilima, and Md Abdul Hannan Miah / Household-Led Heat Resilience Measures

Through the PLASPIN Model, Sumaya and Effat partnered with local communities at Shah Poran to tackle waste through a reward-based recycling system, recycling over 115 kg of waste with women leaders managing household plastic collection, data entry, and sorting. | Photo: Sumaya Rahmatullah and Sanjid / MAP 4 RESILIENCE

Equally important, CRF demonstrated a scalable model for climate resilience across the Asia-Pacific region. By combining open mapping technologies with local leadership and community ownership, the fellowship showed that effective climate action does not require large-scale infrastructure or top-down control. It requires trust, representation, and sustained investment in people who are already adapting every day.

As climate risks continue to intensify across the region, the lessons from Bangladesh are clear. Resilience is not built solely through data or funding, but through relationships—between youth and communities, between local knowledge and open technology, and between grassroots innovation and institutional support.

The Climate Resilience Fellowship did more than support projects. It invested in youth as innovators, connectors, and leaders, capable of designing solutions that respond to real risks—from water scarcity and heatwaves to information gaps and invisibility on the map. In doing so, CRF offers a hopeful blueprint for inclusive, localized climate action across Asia-Pacific—one where investing in youth and innovation is not optional, but essential.

This article was written by Mikko Tamura, with editorial contributions from Tony Liong.

Cover photo credit: Sumaya Rahmatullah / MAP 4 RESILIENCE