How AI Speeds Up Emergency Mapping: Testing fAIr with Shapashina

Publié par Pauline Omagwa • 27 janvier 2026

When a landslide hits, humanitarian responders need maps of the affected areas. Where are the buildings? The roads? Where are the health facilities located? This information helps coordinate rescue efforts, deliver aid, and plan recovery.

However, creating detailed maps takes time. A mapper might spend an hour and a half tracing buildings from satellite images for just one small neighborhood. When disasters strike, communities don't have that time.

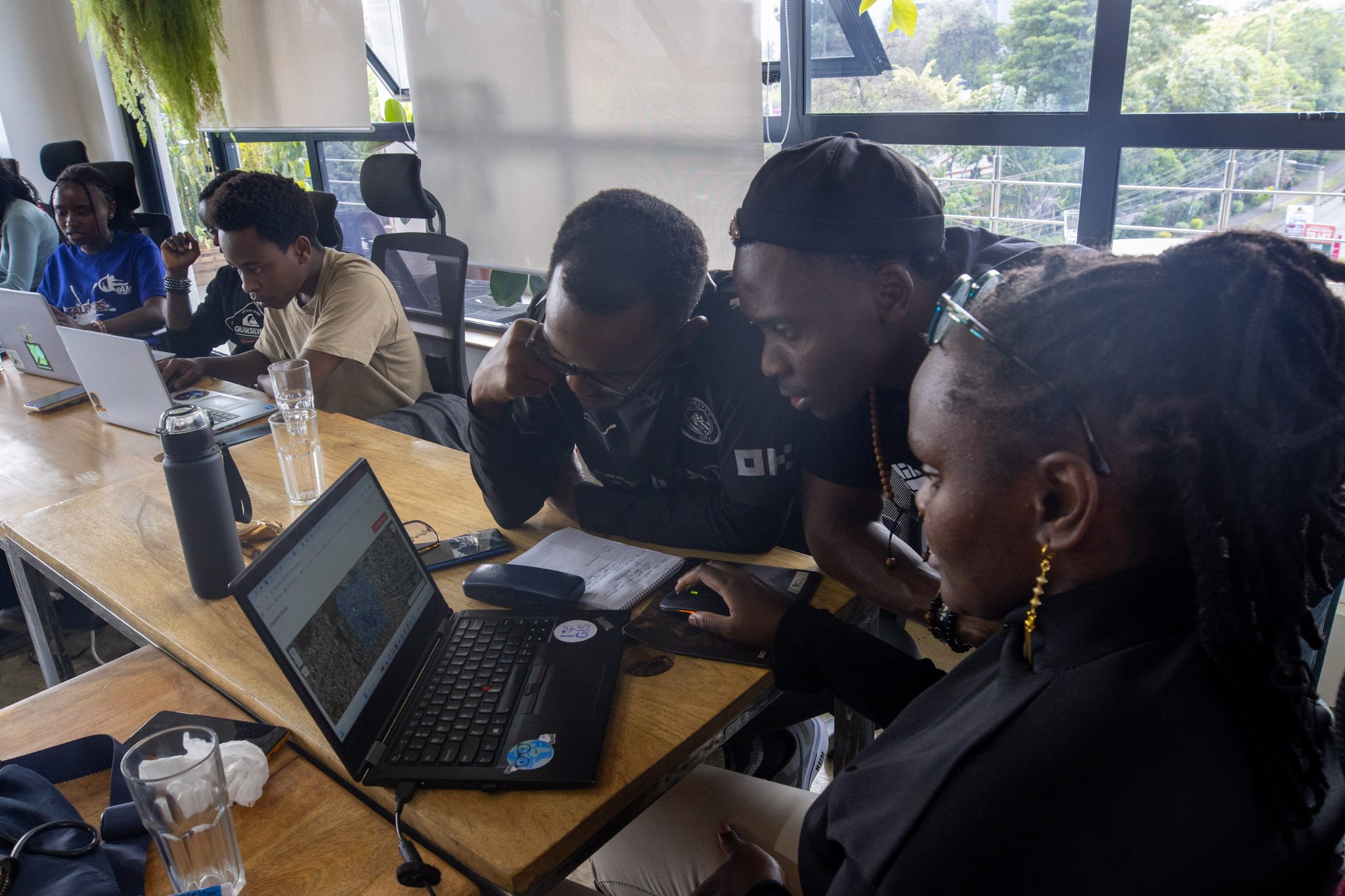

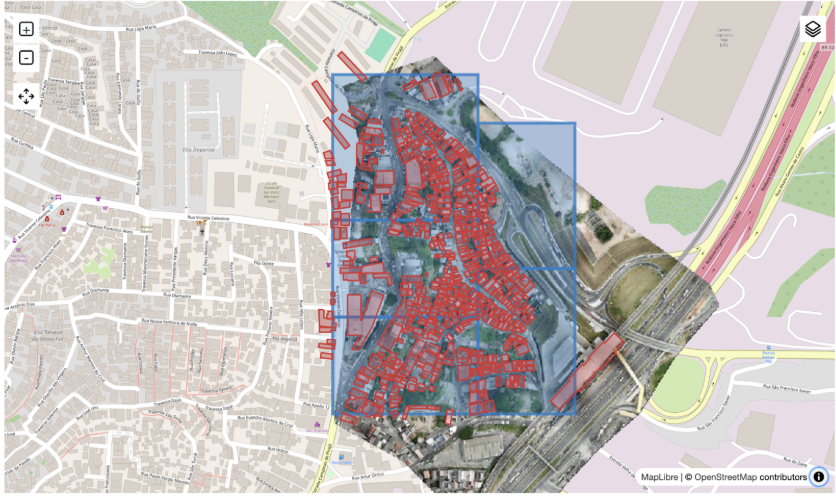

The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) built fAIr to solve this. How it works is that mappers show fAIr what a building looks like in the area they are mapping from a satellite image. It then uses the examples to find similar buildings across hundreds of other images. The mapper reviews what fAIr produced, correct mistakes and adds the accurate data to the map. In December 2025, HOT held a workshop in Nairobi to test fAIr with mappers from OpenStreetMap (OSM) Kenya. Shapashina Malei was one of the twelve participants.

One mapper becomes many.

Shapashina is a Geographic Information System student at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology in Kenya. She volunteers through HOT's Tasking Manager—a platform where humanitarian organizations post urgent mapping needs.

Over the two days she learned to use fAIr. She manually traced some sample buildings to teach the tool what to look for. Once fAIr learned the pattern, it detected similar buildings across a much larger area. "I can just key in my things and I'll be able to obtain my data in just a few seconds." Shapashina stated. Shapashina was clear. "We are required to be there as humans so that we are able to correct whatever AI has not been able to recognize." By the end of the workshop, she was already planning ahead. "We have a community in our school. I'm going to show them this "

When It Matters

For emergency responders, speed is everything. Shapashina knows this. "Those ones are very time-sensitive," she said, talking about disaster response projects. "People need to contribute to them faster because they are to be used in cases of emergencies."

She normally spends ninety minutes mapping a small area. If fAIr drops that to seconds, she can map more while balancing her studies and help respond to more emergencies.

After a disaster, days versus weeks of mapping determines how quickly responders reach affected communities. When landslides occurred in Elgeyo Marakwet, the speed difference in her current mapping task allowed responders to act sooner.

Learning from Other Mappers

What excited Shapashina most was seeing what other mappers had already built. When a mapper in Nairobi trains fAIr to recognize tin-roofed houses, a mapper in Mombasa, Kenya, can utilize that same training instead of having to start from the beginning. Mappers share their work, adapt it to their areas, and build on each other's efforts.

fAIr includes a library where mappers can access and use training that others have created. When a Nairobi mapper trains the tool on tin-roofed houses, a Mombasa mapper can use that same training. Instead of everyone training fAIr from zero, mappers build on each other's work. Improving It

Shapashina also showed us where fAIr needs work. Some controls weren't clearly explained. She had to experiment to figure out what they did. Set one slider too high and the tool missed buildings. Too low and it flagged things that weren't buildings. "It was not accurate the first time I was using it. But it was because of the values that I used in my settings," she said.

The workshop also showed us exactly what needs fixing: clearer explanations of how the controls work, better instructions for when to use which settings, and more reliability when mappers are training the tool on their sample buildings. We're addressing these specific issues based on what Shapashina and the other participants told us didn't work.

HOT tests tools with communities, learns what doesn't work and fixes it before wider adoption. Shapashina's honest feedback about the confusing controls improves fAIr for every mapper who will use it in the future.

What Happens Next

Twelve mappers in Nairobi now know how to use fAIr. They also left with marketable skills. Humanitarian organizations, governments, and development agencies hire mappers who can work with satellite images and train detection tools.

Shapashina will also train her school community. She'll use fAIr when disasters strike. When she hits problems we didn't anticipate, she'll tell us. When one mapper trains others, the overall capacity of the team grows. When the next emergency hits, those twelve mappers will be ready and so will the ones they train.