GrabBike Drivers Support Disaster Managers Identify IDP Camps in Bali

Posted by Biondi Sanda Sima • Oct. 24, 2017

Grab Indonesia, a ride-hailing startup, started an unprecedented initiative in the humanitarian world. Partnering up with Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT), GrabBike drivers were trained to use an Android-base app that can identify evacuation routes and IDP camps, in addition to reporting urgent needs from these camps.

BNPB-HOT-Grab Discussed Strategies to Collect Fata from IDP Camps. HOT Indonesia/Biondi Sima\

Geo Data Collect (GDC), the name of the app, functions as a simple, easy to use online form that can also be used to track bikes' routes, record GPS coordinates, capture pictures and videos, and enlist more descriptive information using templates customized by disaster managers to fit data requirements from the field. GDC was developed by HOT, with the support of DMInnovation and the Australian government.

GDC by HOT has already been integrated to Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana (BNPB)'s server for data localization. Collected data can then be recapped as tables of needs from IDP camps, images to give an idea how the camps look like, as well as maps and geolocation reported by the app users.

Spatial data with maps, images, and tables of needs are extremely useful for government, humanitarian organizations, and volunteers working on the field when responding to and mitigate disaster risks. A lot of these places might not be identifiable on other existing map platforms. Having them marked by Grab Drivers will give richer information to disaster managers as they are covering for the distribution of basic needs, such as medicine, food, clean water, and other specific needs.

[Pic 2. 144 Camps were Identified by GrabBike Drivers. BNPB/Teguh Harjito]\

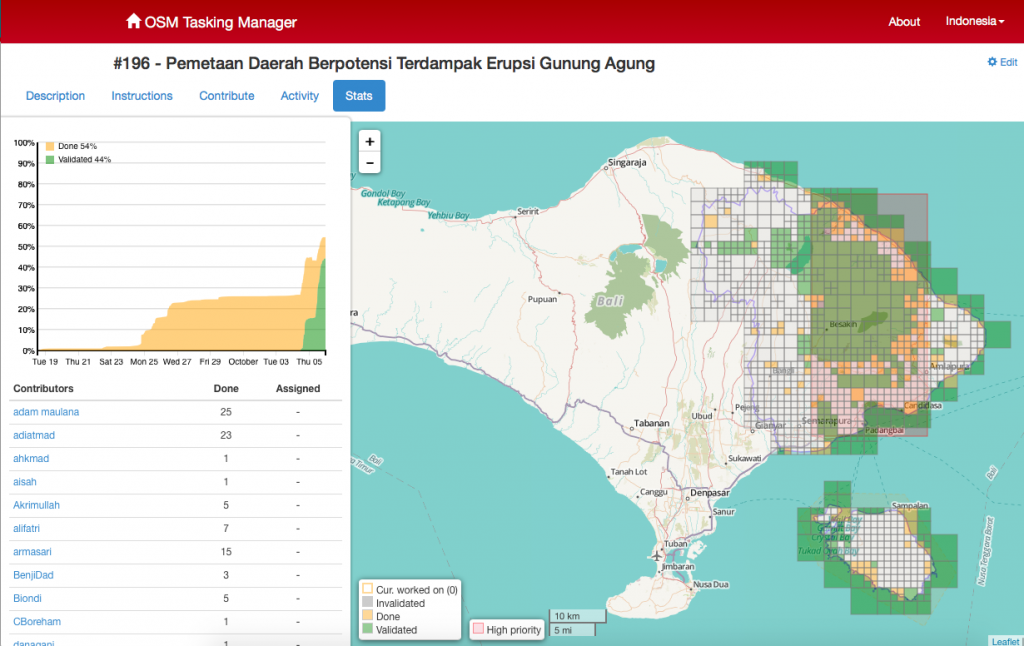

As a pilot project, HOT started with communicating the initiative with around 50 drivers in Bali. This location is picked following the massive outflow of refugees from surrounding Mount Agung whose alert on seismic activities and possible eruption was spiked to the highest level in September 22, 2017. In October 5, 18 GrabDrivers underwent trainings on how to use the app.

Together with HOT trainers, the drivers swept across Klungkung and Karang Asem--the two areas with the highest concentration of around 255 IDP camps--to find where the needs are. Drivers finalized data from more than 20 locations and enlisted their existing needs with the help of local camp coordinators in less than three hours during the first round of survey. Within the first week, the drivers were able to gather information from over 144 camps. Grab drivers were also requested to identify livestock owned by refugees and the situation in local clinics and health facilities to prevent the outbreak of communicable diseases from these livestocks.

[Pic 3. One of the Coordinators Pointed at the Number of Female Refugees at a Camp in Bali. HOT Indonesia/Biondi Sima]\

There are three reasons why the use of GDC by Grab for refugees identification could be an answer to the needs on the field.

Firstly, Grab employs a massive number of drivers, spread accross the streets almost 24 hours a day, all of which are already accustomed to using mobile apps for their daily work. Grab drivers are most likely more familar with where major public facilities are located and the routes leading to them, as they frequently deal with navigation system while commuting. On the other hands, humanitarian workers dealing with ongoing crisis might be dispatched from somewhere else, not familiar to the field in question. Particularly true in remote areas, a lot of road networks and buildings are not mapped. This means relying independently on publicly available map applications might not suffice.

Secondly, data collections from refugee camps are usually done manually, using paper and pen. Such reporting mechanism takes time before the reports can arrive at the table of disaster managers, where vital decisions are made. Data recap and analysis have to be reinputted manually, which eats up even more time. In the context of ongoing crisis, where every second counts at saving and responding to needs, such delays to data-driven decision making could mean increased mortality and suffering. Instant messaging tools, such as Whatsapp, used by many government stakeholders to relay information, may shorten the time needed to collect data from different places, but lacking at features that allow instantaneous analysis, such as geolocations, maps, and navigation routes. With instant messaging, data recap should still be done manually, which would still be resulting in delays, before accurate decisions can be made.

Lastly, Grab has presence in over 75 cities, and is planned to scale-up to 100 districts in Indonesia by 2017. Many of these places overlap with priority districts listed under 136 priority districts of BNPB's RPJMN, a comprehensive list of areas with high vulnerability to disaster. Indonesia is a country with over 10% risk index (UNU-EHS, 2016). Synchronised efforts from private and non-governmental sectors are crucial to build capacity at responding to disaster crises in these hundreds of places.

This colaboration between BNPB, HOT Indonesia, and Grab is an exemplary public-private-non-profit partnership at tackling social problem using innovative technology, and crowdsourcing from community's active participation, in this case, the bike drivers.